|

The old man swayed back and forth on the bench before the wooden pipe organ, his arthritis-crippled fingers playing over

the silent keys. Behind and above him, with a hiss of gas, flames suddenly erupted. Dirt fell loosely from the ceiling, the

nearby slowly-turning water wheel caught fire and improbably halted. With thudding finality, a beam fell.

"Cut!" the director called. "Hurry up, you guys, right away." Even before he spoke, the special effects

crew dashed up to the raised area of the dungeon set with fire extinguishers and quenched the flames on the floor. Those

on the walls were turned off backstage

The old man, almost unnoticed in the busy hustle, made his way off the platform to the ever-present wheelchair. "Thanks,

Boris," the director said. Boris Karloff had finished the final scene of House of Evil, one of the last two movies

he would ever make. And still dizzy over being there, I stood in the background and watched.

I had first encountered Karloff in person about a year before he made those last four films, when I was invited to Milt

Larsen's wonderful Magic Castle to attend a press reception for the actor, publicizing his record album, An Evening with

Boris Karloff and His Friends. I was not introduced to him at that time but was one of several more-or-less anonymous

faces firing questions at him in one of the little magicians' showrooms at the Castle. Many of the questions were familiar,

and so were some of the answers. He seemed then to be a kind, thoughtful man, but also seemed to be very, very tired.

Then, in 1968, Boris Karloff returned to Los Angeles to make four films in five weeks in a co-production deal between Azteca

Films of Mexico and Hollywood's Columbia Pictures. Fortunately, in a sense, I was out of a job, so when Forry Ackerman invited

me to go to the sets with him, I had the time to do it. The first day, I met Luis Enrique Vergara, the Mexican producer

of all four films; we hit it off very well, and he invited me to come back as often as I liked. I took him up on the offer,

inviting fellow fan Jim Shapiro along one time, Jon Berg another. I didn't want to become a pest, so I actually stayed away

on several days I could have gone.

A Monster Kid's dream come true. Bill Warren (before he discovered Hawaiian shirts) with the Uncanny Karloff on the set of

The Fear Chamber.

That first day, I looked around the cramped soundstage, trying to find Karloff. As unlikely as it seems, he was hard to

spot initially, as he was seated in his wheelchair, obscured by set workers standing around him. No one was speaking to him,

and he appeared to be quietly drowsing. He was costumed for the part of the scientist of The Fear Chamber.

When I finally worked up the courage to speak to him (after being introduced by Forry), Karloff was quite friendly, but seemed

to have some trouble speaking. The weather was stifling hot and as he had only one half of one lung to breathe with, speech

was not easy for him. He answered my few questions, some of which I am sure he had been asked many times before but he responded

to all, graciously and honestly. He autographed some stills for me as well, but since I could see that even this minor exertion

was an effort, and since I was intensely nervous and almost terminally shy, I took my leave.

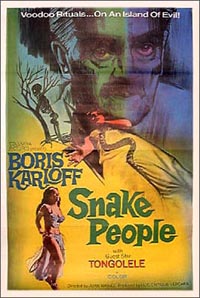

I was on the set of Isle of the Snake People only briefly, though in a sense I am in the movie: I was creeping around

the set behind the flats when the director called action. If the wall could be erased, you could see me, standing six feet

from Karloff. (Robert Bloch later told me the same thing happened with him on the set of Psycho: if you could see

through the fake walls of one of the sets, there you'd find Bob Bloch.)

Arthritis and emphysema can't stop trooper Karloff from valiantly performing without the aid of a wheelchair when the cameras

roll for House of Evil.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Karloff signs copies of Famous Monsters of Filmland for editor Forrest J. Ackerman as Bill looks on.

I was on the sets for several days each for the third, House of Evil, and for the fourth, The Incredible Invasion.

He may have recognized one of the electrical gadgets on the set; it was one of Kenneth Strickfaden's devices, and had been

used in Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, among many others.

Again, when I arrived, Karloff was seated to one side, out of the way, holding an oxygen mask to his face and studying his

lines. (All his career long, he prided himself on being a quick study.) Jon Berg today a special effects expert and I

hovered around him, not talking but merely pleased to be in his presence. We also half-heartedly tried to keep visitors to

the set from bothering him.

For example, a mother who was on the set dragged her son up to the tired old actor and said, as if Karloff weren't there,

"See? He played Frankenstein." The unimpressed boy said, "You mean Herman Munster?" As if he hadn't

heard them, Karloff at first didn't glance up. But when the woman spoke directly to him, he raised his head and smiled.

He spoke, as before, kindly and sincerely.

My respect for him as a craftsman and a hard worker went up when he was called to the set for his scenes. He arose from

his wheelchair, shedding twenty years in the process; despite the leg braces he wore, he walked to the set unassisted and

took his place. The chance to work, even under these circumstances, washed the years away. In the scene, Karloff was required

to bolt a door and suddenly pain distorted his face and he leaned heavily against the wall. There were audible gasps all

around the stage; Jon Berg stepped forward, hoping to help. I found that I had done the same. Then we all realized that

he was simply acting. Our concern for him, our apprehension over his courage, our awareness of his weakened physical condition,

and a lifetime of loving the man on screen had made us all want to help.

By this time, I'd seen him shoot many scenes with multiple takes of each, and I'd noticed something curious. I always assumed

that actors would repeat a performance exactly, in each take (and most do that), but Karloff varied each take slightly. He'd

move his head differently, change his gestures, alter the inflections of the lines.

I talked with him about this later on. He said that he had studied the script carefully, as always, so he'd know about his

character not only from his own lines and actions, but from what the other characters said and felt about his character. He

wanted to bring his part fully to life, knowing that in a fantastic movie, believability is of major importance. To produce

believability for the audience, he had to achieve it for himself. That was one reason he varied his performance from take

to take, while remaining within the boundaries of the character as he had interpreted them. "I've done it all my film

career," he told me. "I've discovered that it keeps one from becoming too stale. This is a very great danger in

working in films." His variations were always in character, and never would present any problems to the editor in fact,

they provided more choices.

Click below to continue

Karloff Page 2

|

|

|

|

|

|