Monster Kid Online Magazine #6

More

|

|

|

|

|

||||

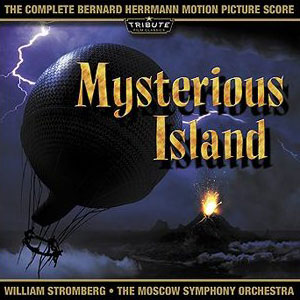

The movie was a show piece for Harryhausen’s stop motion creatures and Herrmann was one of the few composers who was up to providing appropriate musical material that could hold its own with the impressive visuals. The composer created a brilliant score, dazzling in its musical invention, textures and themes. Sadly, unlike the previous two films, there was no commercial soundtrack album released. Those who had been impressed with the music waited and waited and waited some more. Except for network television broadcasts, then local telecasts, there was only silence. Luckily, Herrmann had success recording various albums of his film music for the London label which featured his non-genre works like Citizen Kane and one album devoted to his work with Alfred Hitchcock. These led to “Fantasy Film World of Bernard Herrmann” a 1974 album that was the first of the London series to deal exclusively with his more fantastic compositions such as The Day the Earth Stood Still, Journey to the Center of the Earth, Fahrenheit 451, and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. In 1976 “Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann” appeared. Then, in 1984, the late David Wishart’s Cloud Nine Records released an album from the original tracks. They were in mono and not all the tracks had survived. Still, it was a miracle to have even this much of the original score. This was somewhat rectified in 1993 when CNR achieved a second miracle and released a CD containing 12 original tracks totaling 42:30, but still missing several cues. However, it was in stereo. As Wishart explained, though the movie had mono sound, the score had been recorded in stereo with four microphones. While it is Herrmann‘s original, the sonics of this recording, as exciting as it is to have, suffers due to the vagaries of storage methods and age which renders it, in today’s parlance, an archival edition. Which brings us to the present and the new recording from Tribute Film Classics (TFC-1001). This is a marvelous debut for a new label, the brainchild of Anna Bonn, John Morgan, and William Stromberg. Many soundtrack collectors will be familiar with the Morgan/Stromberg recordings for Marco Polo, then Naxos. With this, and their simultaneous release of Herrmann’s Fahrenheit 451, they stand at around three dozen album releases of notable film music given the loving care they so richly deserve.

The use of descriptive program music continues in several of Herrmann’s cues. Throughout the “Clouds” series, “The Clouds A-E,” we are treated to various musical interpretations of ascent and descent, tumultuous thunder, and the sense of being feather-light. In “The Giant Crab” Herrmann uses short, stabbing musical notes, amidst dense orchestration to suggest both the scuttling of that creature and its enormous mass. In “The Bird,” a sequence in which a prehistoric Phorarhacos attacks the survivors, Herrmann not only paints a musical picture of a giant fowl, but turns a potentially unintentionally comic moment into one that mixes humor and menace. It raises the question if this sequence was originally planned to be comic in tone.

There are other musical colors. Early in the film Herrmann introduces “The Battle,“ a martial theme the composer will reuse in other aggressive settings such as “The Pirates” and “Gunsmoke” before re-purposing it as a suspense motif for “The Raft” and “The Divers.” The gentle “Exploration,” “The Volcano,” and “The Stream” are full of awe and wonder but also describe an ineffable poignancy, a lament almost for this island. In fact, these cues and others seem designed to create a yearning not just for something gone but something tragically lost. The highly atmospheric horn fanfare in “The Island,” a forlorn piece with the foreground horns echoed by others in the distant, appears elsewhere. It’s there during the discovery of “The Cliff”and eventually alerts us that “The Sail” of the pirates has been spotted. Although it’s primary purpose seems to create the feeling that the survivors are alone on this island, it could also be a bit of musical foreshadowing, since all evidence of men on the island appears due to visits by the pirates.

William Stromberg conducts the Moscow Symphony Orchestra in a virile, forceful manner yet catches the nuances of the more delicate moments in the score. He has an impressive array of instruments at his command and they are arranged across the soundstage for maximum stereo listening impact. This is a recording to be played at high volume and may possibly raise the hair on the back of your neck. It is a rich and satisfying recording from every standpoint. To make matters even better, there are a half dozen cues with music cut from the film and one cue that didn't make it into the finished score at all.

Each of the earlier recordings of the Mysterious Island score have their merits and are worth having. One is a later recording by the maestro himself and another represents the maestro’s original recording. But if only one version could be owned, for its completeness, fidelity to its composer and magnificent sonic impression, the recording most worth having would be this edition from Tribute Film Classics. Ryan Brennan |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

Mysterious Island

Mysterious Island

“Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann” included music from The Three Worlds of Gulliver, Jason and the Argonauts, and Mysterious Island. This last title was a godsend for fans who had been waiting fifteen years to own a piece of this score. The sound was big, the orchestra lush. But there was still a problem. In his latter years Herrmann had taken to conducting in a tempo slower than that employed in the films. This album was no exception. Those dissatisfied with the 33 1/3 rpm tempo, which was deemed too slow, tried adjusting their turntables to 45 rpm, which tended to be too fast to be satisfying. And since Herrmann had died the previous year, there seemed little hope we would ever hear the music properly.

“Mysterious Film World of Bernard Herrmann” included music from The Three Worlds of Gulliver, Jason and the Argonauts, and Mysterious Island. This last title was a godsend for fans who had been waiting fifteen years to own a piece of this score. The sound was big, the orchestra lush. But there was still a problem. In his latter years Herrmann had taken to conducting in a tempo slower than that employed in the films. This album was no exception. Those dissatisfied with the 33 1/3 rpm tempo, which was deemed too slow, tried adjusting their turntables to 45 rpm, which tended to be too fast to be satisfying. And since Herrmann had died the previous year, there seemed little hope we would ever hear the music properly.  Matching the crashing surf over which the titles scroll, “Prelude” assaults listeners, lifting them on a wave of music before dropping them into the churning whitewater, the cymbal crashes signifying a clash of elemental forces with puny humankind caught in the middle, for this is a movie as much about man vs. nature as it is man vs. man. And if a main title is meant to set the tone for an entire movie then audiences knew they were in for a spectacularly grand adventure.

Matching the crashing surf over which the titles scroll, “Prelude” assaults listeners, lifting them on a wave of music before dropping them into the churning whitewater, the cymbal crashes signifying a clash of elemental forces with puny humankind caught in the middle, for this is a movie as much about man vs. nature as it is man vs. man. And if a main title is meant to set the tone for an entire movie then audiences knew they were in for a spectacularly grand adventure.  Herrmann paints “The Giant Bee” in the manner of Rimsky-Korsakov, with the buzzing of the insect, but goes one better with the impression of their fluttering wings. “Attack” sounds like nothing else but the firing of the pirate ship’s battery and the explosion of cannonballs. Both “The Octopus” and “Underwater” draw on similar orchestral groupings from Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef, the harp still present but most of these cues in lower registers to not only suggest depth but a darker and more foreboding menace. Musically, it is possible to hear the Cephalopod’s tentacles unrolling and writhing. “The Ship Rising” struggles and strains musically as the ascending musical line successfully lifts the pirate ship from the ocean bottom.

Herrmann paints “The Giant Bee” in the manner of Rimsky-Korsakov, with the buzzing of the insect, but goes one better with the impression of their fluttering wings. “Attack” sounds like nothing else but the firing of the pirate ship’s battery and the explosion of cannonballs. Both “The Octopus” and “Underwater” draw on similar orchestral groupings from Beneath the Twelve Mile Reef, the harp still present but most of these cues in lower registers to not only suggest depth but a darker and more foreboding menace. Musically, it is possible to hear the Cephalopod’s tentacles unrolling and writhing. “The Ship Rising” struggles and strains musically as the ascending musical line successfully lifts the pirate ship from the ocean bottom. One of the highlights is also incredibly short. Clocking in at just :41 is “Captain Nemo,” a dynamic short theme that accompanies one of the great character entrances in film as Nemo rises from the water in his self-devised deep sea diving outfit. Musically, this piece could as easily have introduced Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still a character no less alien in appearance than Nemo.

One of the highlights is also incredibly short. Clocking in at just :41 is “Captain Nemo,” a dynamic short theme that accompanies one of the great character entrances in film as Nemo rises from the water in his self-devised deep sea diving outfit. Musically, this piece could as easily have introduced Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still a character no less alien in appearance than Nemo. The CD includes a handsome 32-page booklet replete with photos and advertising materials from the film. There are words from composer/conductor William Stromberg, executive producer Anna Bonn, film historian Bruce Crawford, some fella named Ray Harryhausen, composer/producer John Morgan, The Bernard Herrmann Society’s Gunther Kogebehn, make-up artist Craig Reardon, composer Christopher Young and composer/conductor Kevin Scott, who wrote the liner notes on the score.

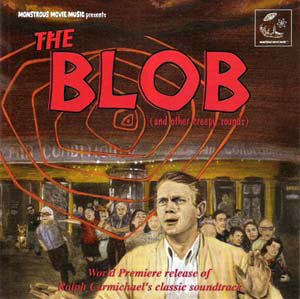

The CD includes a handsome 32-page booklet replete with photos and advertising materials from the film. There are words from composer/conductor William Stromberg, executive producer Anna Bonn, film historian Bruce Crawford, some fella named Ray Harryhausen, composer/producer John Morgan, The Bernard Herrmann Society’s Gunther Kogebehn, make-up artist Craig Reardon, composer Christopher Young and composer/conductor Kevin Scott, who wrote the liner notes on the score.  The Blob (and Other Creepy Sounds)

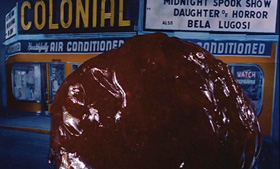

The Blob (and Other Creepy Sounds) Like some other films of the period, teenagers were the chief characters. Portrayed by emerging star Steve McQueen and Aneta Corseaut (later a regular on THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW), these teens aren’t rebels but rather decent kids who are not believed when they try to convince authorities that a malevolent force threatens their community.

Like some other films of the period, teenagers were the chief characters. Portrayed by emerging star Steve McQueen and Aneta Corseaut (later a regular on THE ANDY GRIFFITH SHOW), these teens aren’t rebels but rather decent kids who are not believed when they try to convince authorities that a malevolent force threatens their community.  Produced by Jack Harris, it was the first of three films with director Irwin S. Yeaworth, Jr., the others being DINOSAURUS! And THE 4D MAN. The color film, reportedly shot for a very modest $120,000, sported some impressive special effects and achieved box office success (one source claiming $4 million, another over $8 million). The following year an imitator, CALTIKI, THE IMMORTAL MONSTER (1959) crept onto screens, and BEWARE! THE BLOB (aka SON OF BLOB), with an emphasis on comedy, followed in 1972. In 1988 a much bigger budgeted remake was released that jettisoned most everything in the original except the small town setting and title monster.

Produced by Jack Harris, it was the first of three films with director Irwin S. Yeaworth, Jr., the others being DINOSAURUS! And THE 4D MAN. The color film, reportedly shot for a very modest $120,000, sported some impressive special effects and achieved box office success (one source claiming $4 million, another over $8 million). The following year an imitator, CALTIKI, THE IMMORTAL MONSTER (1959) crept onto screens, and BEWARE! THE BLOB (aka SON OF BLOB), with an emphasis on comedy, followed in 1972. In 1988 a much bigger budgeted remake was released that jettisoned most everything in the original except the small town setting and title monster. Carmichael supplied the Blob with a theme of its own, of sorts. He doesn‘t consistently maintain it but often throughout the score the listener is musically alerted to the creature’s presence by the use of the bass played in extreme low register. In fact, while different, it may remind one a bit of a similar, later use by John Williams in JAWS.

Carmichael supplied the Blob with a theme of its own, of sorts. He doesn‘t consistently maintain it but often throughout the score the listener is musically alerted to the creature’s presence by the use of the bass played in extreme low register. In fact, while different, it may remind one a bit of a similar, later use by John Williams in JAWS.